Law enforcers report drug arrests on social media with sassy hashtags; experts say that reinforces stigma, inhibits treatment

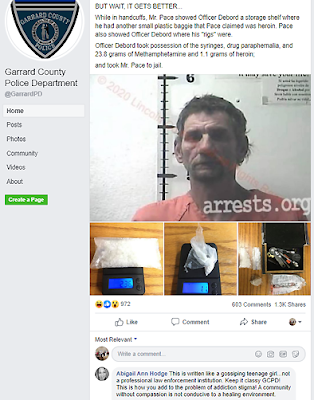

Screenshot of Facebook post; click on the image for a larger version.

—–

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

Some Kentucky law-enforcement agencies are getting sassy in their social-media posts about the disease of addiction, a practice they say attracts a larger audience for their work against drugs and other banes of their communities.

But health advocates say the practice is dehumanizing, discourages people with substance-use disorders from seeking help, and perpetuates public stigma, Bobbie Curd reports for the Danville Advocate-Messenger in an article titled: Hashtag stigma: Addiction experts warn against trend of using humor in reporting drug arrests.

Curd details several cases. One involved an intoxicated man who reported a stolen laptop computer, and told the responding officer that he wanted to go to jail, eventually saying he wanted to be with his girlfriend, who was serving a five-month term. Then he pulled out a spoon, syringe and a large amount of suspected methamphetamine, and was arrested.

The Garrard County Police Department posted a release on its Facebook page about the incident Jan. 6 with the headline “True Love” and a subhead “BUT WAIT, IT GETS BETTER,” above the drug revelation.

“Hashtags on the post included “#LoveWins, #IsThisMTVCribs, #LemmeShowYouAround, #LoveANDmethAreInTheAir, #WhereCupidAt,” and “#CheckOutMyStash,” among others,” Curd writes. After her story appeared, the hashtags were removed.

Earlier, Garrard County Judge-Executive John Wilson told Curd that a “younger moderator” created the tags, which mimicked what other agencies had done. He said he was responsible, and wants to humanize police. “You see a lot of animosity towards law enforcement, so anything we can do to make the department a little more relatable” helps, he said, adding that he did not intend to make light of the case.

Wilson said his headline and subhead did not editorialize, and “bringing publicity to what the officers are doing is helpful. It’s not intended to poke fun.”

Curd reported, “Out of the 572 comments on the post, almost all are from people making jokes. The post has been shared 1,300 times. Only a handful of comments question the wording of the post.”

She added that other police agencies in the area have used similar catchy hashtags, and some officers she interviewed told her that they may have copied the practice from the Louisville Metro Police Department.

Curd reports that the Louisville police posted: “On Christmas Eve Eve, our Major Case Unit 1 in our Criminal Interdiction Division was creepin’ and peepin’ on a known drug trafficker. What do alleged drug dealers do on X-mas Eve Eve? Well, they go bowling, of course.”

Curd notes that the post detailed an incident involving a “large currency transaction” that speculates that it may have been over a person who “lost a bet not picking up a 7/10 split.” She gave the hashtags: #BowlingPunTime, #SomeAlleysAreDangerousYouCouldEndUpInTheGutter,” #YouKnowTheTagsAreComingInHot, #BowlingWitMyHomies” and #WhenWeSeizedTheMoneyYouCouldHearAPinDrop.

Sgt. Lamont Washington, the department’s chief spokesman, told Curd that the department’s more comedic approach helped increased its Facebook followers from 5,000 in 2016 to 130,000 today, a “valuable law enforcement asset” that has spurred apprehension of suspects.

“And the hashtags on drug seizes, we have people who look at our page now that don’t know anything about policing, and we are able to educate them” with such information as quotations of state law.

But Washington also told Curd that even with “all the fun,” the department never posts mugshots, unless they have an active warrant for someone and want the public’s help; tries not to lose sight that the person involved is a family member; and strives not poke fun at addiction or use slurs like “crackhead” or “doper.”

Newspapers follow suit

After the Garrard County post went up on a Monday, the Garrard Central Record, the weekly newspaper in Lancaster, printed a story that Thursday with the headline, “Might as Well Face It, He’s Addicted to Love.” Editor-Publisher Ted Cox declined to comment, Curd reports.

She asked Al Cross, director of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues at the University of Kentucky about it and he said, “This is one reason I did a Covering Substance Abuse and Recovery workshop in November for journalists.” One session explained why it is important to not use stigmatizing language when reporting on addiction.

Cross, who is also the editor and publisher of Kentucky Health News, said reporters are largely uncomfortable with doing enterprise reporting on the subject and “often default to the law-enforcement narrative. When the law enforcement narrative turns into mocking people with the disease, that is an inappropriate narrative to adopt.”

In adjoining Mercer County in July, the sheriff’s office made an impressive meth bust, Curd reports, posing hashtags included #HugeMethsquitos, #BreakingBad, #HideYaDope, #YouMadBro, #gameon, #YouOweMoneyNowBruh, and #NightShiftLitTho, among others.

But this trend isn’t being followed in Danville, where Asst. Police Chief Glenn Doan told Curd that social-media posts should only be used to inform the community of newsworthy events. “They should contain a basic overview of the incident and all related information that should be deemed pertinent,” he said. “In most cases, they should not contain personal opinion or satire.”

Boyle County Sheriff Derek Robbins agreed. “I don’t think it’s our place to do that,” he said, telling Curd that such posts are not professional and can cast a negative light on the agency. “You have to maintain a sense of professionalism,” he said. “You don’t dehumanize them.”

Jessica Buck, a local public defender who stressed that her comments represented her own views and not her department’s, told Curd that the practice “creates a divide between the community that we’re serving. It takes someone at their very worst, and not only does it share something that’s at the lowest time in their life, it mocks them.”

Robert Fox, who is in recovery from his addiction and is the director of community outreach at the Shepherd’s House, an outpatient treatment center in Danville, told Curd that such posts create a feeling of “It’s us against the world” and “make people like me seem less-than, to keep us in our place. … We go out every day and work with employers to get them to realize this is a disease, and that these are normal people.”

Tanith Wilson, vice president of Shepherd’s House and sober 13 years, called the trend “sad and heartbreaking.” She said it can create a pack mentality online, with “heinous comments like ‘lock them up forever,’ or ‘just let them die.’ I’m very comfortable sharing my past, especially due to what I’m doing now, but it still makes me feel less than human when I read those comments. It’s a terrible, awful feeling.”

Kathy Miles, coordinator for the Boyle County Agency for Substance Abuse Police, told Curd that people who struggle with addiction shouldn’t have their “whole persona encapsulated in their addiction like this, or made light of,” partly because it discourages them from getting treatment. “Law enforcement and the media have incredible power to help people get treatment,” she said.

Don Helme, who is running a health-communication campaign in an $87 million grant-funded project at UK to reduce drug overdoses in Boyle and 15 other counties, told Curd, “It has a chilling effect on people seeking help. They become ashamed, fearful and angry. This sort of stigma in these hashtags — it’s heartbreaking.”