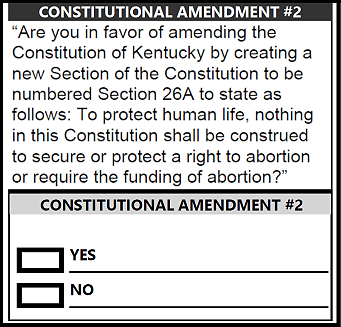

Abortion question on Kentucky’s Nov. 8 ballot may be confusing, but it becomes clearer when you look at the possible outcomes

By Al Cross

Kentucky Health News

FRANKFORT, Ky. – What would it mean if Kentucky voters changed the state constitution Nov. 8 to say that nothing in the document shall be construed to secure or protect a right to abortion, or funding of it?

It means Kentucky judges would not be allowed to find in the state’s basic law the same sort of right that the U.S. Supreme Court found in the federal constitution almost 50 years ago – and erased this year in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case.

Passage of the amendment would leave abortion law up to the General Assembly. The legislature put the amendment on the ballot because legislators thought some Kentucky judges might construe the state constitution’s rights to privacy, self-determination and religious freedom to guarantee that women have at least a limited right to abort a pregnancy.

That’s pretty much what Jefferson Circuit Judge Mitch Perry did this summer when he issued an injunction blocking Kentucky’s “trigger law” banning almost all abortions. The law had taken effect June 24, when the Supreme Court overturned its 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. Perry’s order was blocked, pending a final decision by the state Supreme Court. The state’s high court delayed oral arguments in the case until Nov. 15, a week after the election.

If voters approve the amendment, the case would be moot. If they defeat it, the court could issue its own version of Roe v. Wade, as state Sen. Whitney Westerfield of Christian County warned a rally of abortion opponents supporting the amendment at the state Capitol on Oct 1. “It does nothing more than prevent our state Supreme Court from creating its own Roe,” he said.

The rally drew counter-protesters, whose most common chant was “Abortion is health care.” They were at the foot of the Capitol’s walkway, while amendment supporters were just in front of the building’s steps, citing largely religious reasons for their stance. Since then, three Jewish mothers from Louisville have sued to block the amendment, saying it would violate their faith’s principles.

In his injunction, Perry cited the religious-freedom section of the state constitution, which says “The civil rights, privileges or capacities of no person shall be taken away, or in anywise diminished or enlarged, on account of his belief or disbelief of any religious tenet, dogma or teaching. No human authority shall, in any case whatever, control or interfere with the rights of conscience.”

Perry said abortion-rights supporters were likely to win a lawsuit based on that and other sections of the state constitution that say Kentuckians have “the right of seeking and pursuing their safety and happiness” and “Absolute and arbitrary power over the lives, liberty and property of freemen exists nowhere in a republic, not even in the largest majority.” Kentucky courts have found in those words a limited right to privacy.

A state Court of Appeals judge blocked Perry’s injunction pending further action, and a fractured state Supreme Court went along with that, so the only legal abortions in Kentucky now are those needed to save the woman’s life or prevent permanent damage to a life-sustaining organ. That is the trigger law’s wording.

(Only three of the seven Supreme Court justices fully concurred; the majority was made by Justice Michelle Keller of Fort Mitchell, who concurred in the result only and wrote a separate opinion, and Justice Shea Nickell of Paducah, who joined in that opinion. Keller, a registered independent who was appointed in 2013 by then-Gov. Steve Beshear, a Democrat, is on the nonpartisan ballot in the 6th Supreme Court District against state Rep. Joe Fischer of Fort Mitchell, who sponsored the trigger law and is running as “the conservative Republican.”)

Opponents of the amendment, including Gov. Andy Beshear, are emphasizing the fact that it would maintain the status quo and make abortion virtually impossible in Kentucky, even in cases of rape, incest or threat to the woman’s health.

“If Amendment 2 passes my granddaughter may not have the right to get an abortion to stay alive,” a woman says in the latest television spot from Protect Kentucky Access, the anti-amendment group. That appears to overstate the case, but the trigger law’s exceptions could be subject to court action and state administrative regulation.

While the trigger law has no exceptions for cases of rape, incest or protection of women’s health, it would not prevent the legislature from adding them to the law; it would only keep courts from doing so.

Opponents of the amendment say the legislature has already made its positions clear. Another law bans abortion after the sixth week of pregnancy, when a fetal heartbeat can first be detected.

The first TV spot from Protect Kentucky Access overstated the effect of the amendment by saying, “Amendment 2 means no abortions, no exceptions.” The speaker was Courtney Bennett, who identified herself as a Kentucky woman who had medical complications, as did her baby, that required an abortion.

“We wanted this baby, but both me and the baby were at risk,” Bennett said. “Kentucky politicians don’t understand: their mandate will put women’s lives in danger. It’s an impossible decision. I can’t imagine a politician making it for me.”

Westerfield told the pro-amendment rally that opponents of the amendment are using “myths and confusion” to mislead voters. He urged them to talk with their neighbors and get yard signs that have a bottom line saying “PROTECT TAXPAYER DOLLARS,” indicating an effort to take the arguments beyond the moral and religious.

Yes for Life, the main group supporting the amendment, has raised about a fifth the money as Protect Kentucky Access but is expected to get much organizational help from churches and religious groups.