By Tara KaprowyKentucky Health News

With the Obama administration offering more funding to improve rural health care, Rural Training Track programs to steer medical students to rural areas are hoping to expand, a move that would benefit underserved areas of Kentucky.

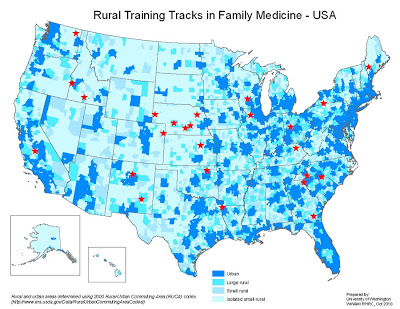

“Over 62 million Americans live in rural America and there is a significant crisis in terms of having access to care for these people,” said Amy Elizondo, vice president of program services at the National Rural Health Association. “There is a very uneven distribution of health care professionals and an acute shortage of primary care physicians in rural areas. If we can recruit and retain physicians to serve rural areas, we improve access for rural America.” (University of Washington map; click for larger version)

RTT programs aim to educate family physician residents in rural environments with the hope they will continue to practice there, Candi Helseth reports in a deailed article for the Rural Assistance Center. “These residency programs are a proven model for addressing rural family physician workforce shortages, with more than 70 percent of graduates praticing in rural areas,” Helseth reports. The first such program started in Colville, Wash., in 1985. There are 25 RTTs in 17 states, including one in Morehead by the University of Kentucky and St. Claire Regional Medical Center. Eight physicians have graduated from the program there since it was established in 2000, five of whom are practicing in Kentucky. Of those five, three have joined the SCR medical staff.

There are similar success stories across the country. In Caldwell, Idaho, 95 percent of graduates have chosen to practice in rural areas over the past 16 years. “We heavily recruit residents who are rural-oriented,” said Dr. Samantha Portenier, a practicing physician and director of the Caldwell RTT. “We’ve had some who were not and we converted them. Part of it was that they really saw where the training we give them and the skills they learn are so needed in rural areas. I emphasize that in rural areas you can specialize in areas that particularly interest you.”

Despite the success, 10 RTT programs have closed in the past 10 years. “Every RTT lives on the edge in terms of funding,” said Dr. Randall Longenecker, who is project director of Rural Training Track Assistance Demonstration Project. “In general RTTs are small, have limited faculty and are vulnerable to personnel changes, a bad year for recruiting, loss of funding and many other factors beyond their control.”

Morehead’s RTT is funded by St. Claire. Residents spend their first year at the UK College of Medicine in Lexington and their second and third years at St. Claire, which is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Education. Carla Terry, St. Claire’s graduate medical education coordinator, acknowledged the difficulty in maintaining an RTT program. “The reason why the RTTs are in jeopardy is that all the faculty that teach them are voluntary,” she told Kentucky Health News. “They are not paid to teach, they still have to keep their patient load. If it were a university program, all the faculty would be paid.”

But St. Claire physicians believe strongly in rural-based education and also see how they can benefit from their investment. “We actually had a physician that when he came here he was interested in starting a residency because he wanted to use that as future recruitment,” she said. “We look at it as training future partners.”

Now, RTTs are under a federal microscope. The health care reform law created the Rural Training Track Assistance Demonstration Project, a three-year pilot program that plans to “collect comprehensive information to better understand the collective forces challenging RTT models and develop solutions that will strengthen existing RTTs and encourage development of new RTTs,” Helseth reports.

The time is ripe, given that more medical students are choosing to be family medicine physicians, up by 11 percent last year and 8 percent the year before. “We have a real opportunity here to redefine the importance of primary care being foundational in rural workforces,” Dr. Ted Epperly, past president and past board chairman of the

American Academy of Family Physicians, told Helseth. “Right now, only 9 percent of physicians are choosing to practice in rural areas while 20 percent of the population lives there. RTTs offer a way to give family physicians a broad scope of practice, which they need practicing in a rural area, and to get them to stay in those rural areas.” (

Read more)