Kentucky is among states with low rates of screening for cancers of the private parts, and thus has a higher death rate from them

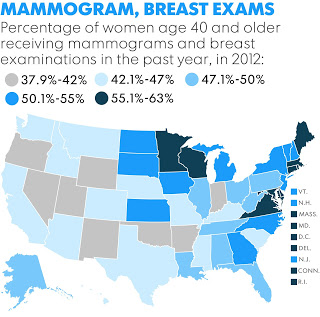

Poor, minority and rural residents are less likely to be screened for breast, colorectal and cervical cancers and more likely to have high mortality rates from the diseases because they are detected too late, says a state-by-state study by USA Today and the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, Laura Ungar reports for USA Today. (USA Today maps)

Kentucky and most other Southern states have some of the highest rates of deaths from screenable cancers, Ungar writes. “While the Affordable Care Act has brought insurance coverage to millions, it hasn’t solved the myriad other problems impeding access to care, such as transportation difficulties, lack of education, inability to take time off from low-wage jobs for medical appointments and shortages of doctors, hospitals and cancer-screening facilities,” Ungar writes. “It hasn’t made all doctors ‘culturally competent’ to effectively care for minority patients.”

And it isn’t expected to get better any time soon, she writes. “Federal funding for cancer screening is in flux. A nationwide program that has provided more than 12 million mammograms and Pap tests for low-income women since 1991 lost $8 million in federal funds in the last five years. And President Obama’s proposed budget for next year cuts $42 million from breast, cervical and colorectal cancer-screening programs on the assumption the ACA will improve access to screening. A bipartisan spending deal hasn’t yet determined specific allocations for particular programs, but previous House and Senate bills restored at least some of the money.”

States with large poor, minority and rural populations need more local programs like one in Kentucky where “a local gastroenterologist with a passion for preventing colon cancer started the nationally renowned Colon Cancer Prevention Project, which raised money and awareness of the disease and pushed for programs such as free screening for low-income, uninsured residents,” Ungar writes. “Since the group started 11 years ago, the screening rate has more than doubled to 69.6 percent—and deaths are down more than 25 percent.” (Read more)