Kentucky has a high premature birth rate, but two programs are reducing it; one stresses home visitations; the other uses data analysis

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

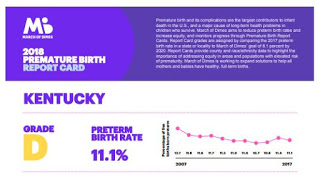

One in nine Kentucky babies are born prematurely, one of the nation’s highest rates – so high that the March of Dimes gave the state a “D” on its 2018 Premature Birth Report Card.

A baby is premature if born before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy, four weeks short of full-term. In 2017, just over 11 percent of Kentucky babies were born preterm. The national average is just under 10 percent, a rate that has risen three years in a row.

Because important growth and development happens during the last weeks of pregnancy, preterm babies are at an increased risk of neurologic, respiratory and digestive problems. Complications from being born early is the main cause of newborn death, says the March of Dimes.

Preterm babies are also at risk for long-term challenges, including behavioral and social-emotional problems, learning difficulties, and increased risk of conditions like attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and increased risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. As adults, they are more likely to have chronic diseases such as heart disease, high blood pressure and diabetes, says UK Healthcare.

The March of Dimes says that while the cause of about half of premature births is unknown, there are common risk factors, including a multiple pregnancy (twins), smoking or drug use during pregnancy, being underweight, having diabetes or having preeclampsia, a condition that is characterized by high blood pressure and the presence of protein in the mother’s urine.

What’s Kentucky doing about it?

Several programs work to lower the number of preterm births in Kentucky.

One is a voluntary home-visitation program called Kentucky Health Access Nurturing Development Services. Kentucky’s HANDS serves first-time, high-risk mothers through local health departments. It received a $7.5 million federal grant in October.

The HANDS program provides assistance to overburdened parents from the prenatal period to the child’s third birthday. It served about 4,000 people in more than 2,000 homes through nearly 56,000 home visits in 2017, according to a Cabinet for Health and Family Services news release.

Research published in the journal Maternal Child Health, shows that participants in the HANDS program had fewer preterm births and low-birthweight babies, and decreased incidences of child abuse and neglect, especially among those who received seven or more prenatal home visits.

The data shows the rate of preterm births among expectant mothers who received one to three prenatal visits was 12.1 percent, above the state’s relatively high average, while the rate for those who received seven or more visits was 9.4 percent, below the national average. Similarly, the rate of low-birthweight babies dropped to 6.5 percent among mothers with seven or more visits, compared to 8 percent who had only one, two or three visits.

The study also found that women in the program had increased access to prenatal care and decreased maternal complications during pregnancy.

The home-visitation program provides the at-risk mother with a family support worker who tailors a plan to meet her needs, including linking participants to community services needed to support a healthy pregnancy and birth. And after the child is born, the program helps families nurture healthy growth and development in the child and teaches them how to create safe homes.

Courtney Embry, a nurse from the Grayson County Health Department, said a family support worker provides education about nutrition in pregnancy and can help expectant mothers sign up for the Women, Infant and Children nutrition program, help them find resources to quit smoking, or help them find transportation to get to their prenatal appointments.

“We see a lot of moms who don’t have transportation, so therefore they are not actually getting to their OB appointments,” she said. “So we will help them find transportation.” She said they do that through community transportation programs, programs that offer gas vouchers or helping them to find employment.

“The HANDS acronym sums up what we do,” said Shelly Lambert, director of early-childhood services for the Lincoln Trail District Health Department. “We are a helping hand for parents. We are there to support them, to help them, to nurture them and help with the development of their child.”

Carter County HANDS coordinator Jana McGlone said one reason the program is so successful is because it explains the “why” of it all, Lisa Gillespie reported for Louisville’s WFPL in October.

“Their doc might say, ‘You need to take your prenatal vitamin,’ but he may not tell them, ‘OK, this is why you should take this’,” McGlone told Gillespie. “When they get that understanding and knowledge, it makes them want to do it more.”

|

| CDC photo |

Another effort to reduce preterm births in Kentucky is a Passport Health Plan program that uses a maternity-analytics platform to identify at-risk mothers. Passport manages the care of more than 310,000 Kentuckians on Medicaid. The analytics were developed by Lucina Health, a Kentucky-based obstetric data management firm.

In just six months, Passport was able to identify 85 percent of its high-risk pregnant mothers during their first two trimesters and provide them with a personalized care plan designed to reduce their risks, according to a Lucina news release. It says the program has reduced early deliveries by 13 percent, earning Passport millions of dollars.

“Identifying and communicating with at-risk mothers as soon as possible is critical to reducing preterm birth rates in the United States,” the release says. “Reducing preterm birth, a national public health priority, can be accomplished by implementing strategies that target modifiable risk factors and provide access to care with potentially high social and financial impact.”

November is Prematurity Awareness Month.