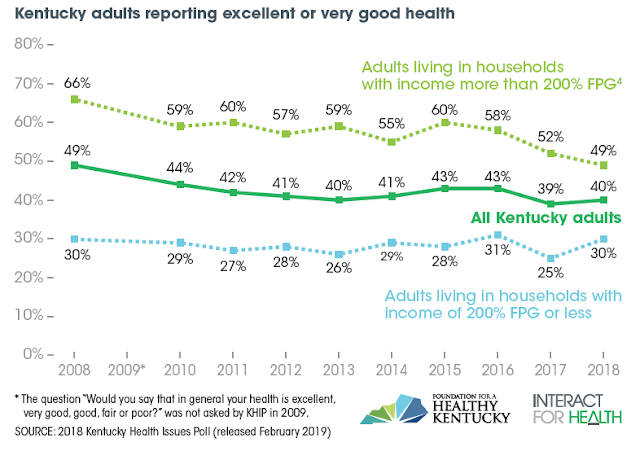

Fewer and fewer Kentuckians over the past decade have told pollsters that their general health is very good or excellent

The number of Kentucky adults who say they’re in very good or excellent health has gradually declined over the last decade, from almost half to only two-fifths.

“Nationally and in Kentucky, the opioid epidemic continues to take a major toll on health and life expectancy across income levels,” said Ben Chandler, president and CEO of the foundation. “Cancer, heart disease and diabetes also shorten lives and reduce quality of life in Kentucky. In many cases, these diseases are completely preventable. But it’s often the case that social and financial circumstances make healthier choices far more difficult for people living on low wages.”

In that year, 1,468 Kentuckians died of drug overdoses, the foundation noted, adding that “Kentucky also has the highest rates of cancer incidence and deaths, and some of the highest rates of heart disease and diabetes in the country.”

“We have a dual issues of declining higher-income population health and the inability to improve health among those living on low incomes,” Chandler said. “These facts must sharpen the focus of policymakers and health advocates to support what works for these populations. Those include smoke-free and tobacco-free laws and higher tobacco taxes, improving nutrition and increasing physical activity in schools, and reducing the cost and improving access to preventive health screenings and substance use treatment.”