Local collaborations help tackle Ky.’s health problems, and can be guided by hospitals’ and health departments’ needs assessments

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

Collaborations in individual communities can play a critical role when it comes to improving Kentucky’s poor health outcomes, largely because those outcomes are grounded in behaviors and unmet social needs at the community level.

That was the underlying message of the June 10 webinar hosted by the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky, “Transforming Kentucky’s Public Health System: The Critical Role of Community Collaborations.”

“There’s a huge need for these coalitions because our health rankings are in the toilet and they’ve been in the toilet for quite some time,” Ben Chandler, president and CEO of the foundation, told Kentucky Health News. “So much of the poor health resides in counties where they have lots of other issues.”

Those other issues are often called “social determinants of health” and include things like housing, transportation, food insecurity, education, healthcare and employment. Researchers have said they account for 80 percent of health outcomes.

Kentucky ranked 48th for health behaviors and 46th for health outcomes in the last America’s Health Rankings report from the United Health Foundation.

Chandler noted that while the U.S. spends twice as much money on health care as other developed nations, it has worse outcomes.

“So what it boils down to is, we’ve got to spend more of our resources working on changing people’s behavior,” he said. “And that sort of thing, I believe can only be done through public policy and at the community level; each community has to be involved.”

Many of these coalitions already exist in Kentucky, but Chandler said there is a need for more and a need to rejuvenate some that already exist.

The Muhlenberg County Health Coalition is an example of one that is thriving.

Jessica Browning, chairperson for the coalition, explained that this coalition was initially created to address the findings of the 2018 community health needs assessment of Owensboro Health Muhlenberg Community Hospital‘s, where she is the marketing director, and includes representatives from all sectors of the community.

Tax-exempt hospitals like Muhlenberg must do community needs assessments every three years, under the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, with the expectation that they use them to create plans to address the identified community health needs. Some do, and some don’t, but Chandler said they are a great tool to guide community collaborations.

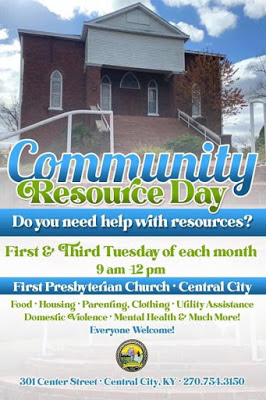

Browning walked through several of the collaborative’s initiatives, including efforts to make information about community and health resources easily available to the county’s most vulnerable residents. The coalition also offers a community resource day twice a month, has found ways to address the county’s homeless and housing issues, and has secured a grant to ensure affordable transportation for people who needed rides to work, school and medical appointments.

The Purchase Area Health Connections coalition in has also created a searchable database of resources in Kentucky’s far west to make it easier for citizens to find the resources they need.

Kaitlyn Krolikowski, network director of the coalition, said two of its largest initiatives are an opioid task force and a transitional care team of community health workers who work to reduce hospital readmission rates. CHWs are not health-care providers but educate people about care and help them get it.

The Purchase coalition’s website shows that it also works on issues around childhood obesity, diabetes, mental health and more.

Krolikowski said the coalition formed when community members realized it would make the best use of their resources if everyone worked toward the findings of a regional community health needs assessment. She said the coalition’s first meeting served as a “catalyst moment” to create different partnerships.