“The setting for adolescent mental health care looks ever more like Dr. Melissa Dennison’s office . . . the next patient arriving every 15 minutes,” says The New York Times. (NYT photo by Annie Flanagan)

—–

May is Mental Health Awareness Month, and that increasingly means looking after teenagers.

“Over the last three decades, the major health risks facing U.S. adolescents have shifted drastically,” Matt Richter of

The New York Times writes from Glasgow, Ky. “Teen pregnancy and

alcohol,

cigarette and drug use have fallen while anxiety, depression, suicide and self-harm have soared. In 2019,

the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a report noting that ‘mental health disorders have surpassed physical conditions’ as the most common issues causing ‘impairment and limitation’ among adolescents. In December, the U.S. surgeon general, in a rare public advisory,

warned of a “devastating” mental health crisis among American teens. But the medical system has failed to keep up, and the transformation has increasingly put emergency rooms and pediatricians at the forefront of mental-health care.”

Richter’s object example is Glasgow and Dr. Karen Dennison, a pediatrician who is now unofficially a part-time psychologist or psychiatrist. His story begins with a 14-year-old girl who told Dennison she was depressed “and had been cutting her arm to relieve her emotional pain. Dr. Dennison suggested therapy, but the girl said she would not go,” Richter reports. Dennison told her, “You need to get off the phone and the computer. When it’s pretty outside like this, put on a bunch of clothes and go for a walk.” She also gave the girl and her mother a prescription for the antidepressant Zoloft, though “She wasn’t sure the girl was clinically depressed.”

“I’d rather they see a psychiatrist,” Dennison told Richter. “But if I’ve got this child and they’re cutting and saying they’re going to kill themselves, I’ll say, ‘Well, I’ll see them today.’ If I call a child psychiatrist, they say, ‘I’ll see them in a month.’” In Barren County, “There are counselors in the schools and therapists in town, including four at Dr. Dennison’s clinic. But they are often booked months out. Psychiatrists are scarce, here and nationwide,” Richter reports. “Over two days, Dr. Dennison had 66 appointments, 20 of them related to mental and behavioral health.”

“The causes of this crisis are not fully understood,” Richter reports. “Experts point to many possible factors. Lifestyle changes have led to declines in sleep, physical activity and other healthful activities among adolescents. This generation professes to feeling particularly lonely, a major factor in depression and suicide. Social media is often blamed for these changes, but there is a shortage of data establishing it firmly as a cause.”

The Washington Post reports, “No group has ever slept as little as the modern adolescent.”

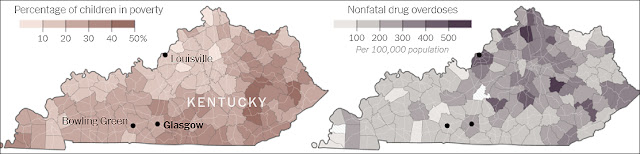

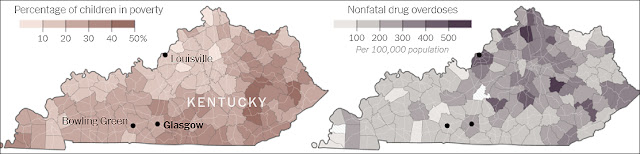

“In Glasgow, a town of 14,000, the challenges are intensified by high rates of drug addiction and poverty and their effect on families,” Richter writes. “Glasgow has a poverty rate of 27 percent and a median household income of $28,000, according to 24/7 Wall Street, a data company that in 2020 ranked Glasgow the poorest town in Kentucky.”

|

| New York Times maps; to enlarge any image, click on it. |

Mallie Boston, executive director of the Boys & Girls Club of Glasgow-Barren County, “said that today’s teens were less physically active and spent less time just hanging out,” Richter reports, quoting her: “If you come to Glasgow right now, the options for what you can do are the movie theater, which is identical to when I was a child, or you have Ralphie’s, the bowling alley. . . . TikTok is such dopamine fuel,” she said. “I worry it is their dopamine.”

Richter interviewed several adolescents at the club, on the condition that he wouldn’t use their names. “Some described struggling with anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts or self-harm,” he reports. “Katrina Ayres, the mental-health coordinator for the local school district, pointed to another change: Students were deeply focused on themselves, selfie-obsessed, which led them to “think everybody is looking at me,” she said. “We’re raising a generation that is very ‘me’ focused. . . . They need to see they’re part of a bigger picture.”