Knowing when to choose hospice care is a challenge; that’s highlighted by Rosalynn and Jimmy Carter’s end-of-life journey

Carter, who was 96, died two days after entering hospice. Jimmy Carter entered hospice in February at the age of 98, outlasting the six-month prediction of life that is typical of people when they enter hospice care.

Rosalynn Carter had a urinary-tract infection that was not responding to antibiotics when she entered hospice, which experts told the Post is among the many reasons people with dementia might switch to hospice care late in the course of the disease.

Bernstein and Keating report that many people follow the same path.

“About half of all people are in hospice at the end of their lives, but more than 25% of hospice patients enroll in the final week, according to 2021 data from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, which advises Congress on Medicare issues,” they write.

Angela Novas, senior medical officer for the Hospice Foundation of America, a nonprofit organization, told the Post that Rosalynn Carter’s experience is not uncommon.

“When people are that age and have a chronic condition like dementia that is progressing, and progressing slowly, there comes a turning point where suddenly the symptoms accelerate exponentially,” Novas said.

Doctors also play a role in delays in enrolling because of “difficulty prognosticating” and patients often wait, hoping for a final experimental treatment to become available, Mamta Bhatnagar a University of Pittsburgh Medical Center physician who specializes in hospice and palliative care, told the Post.

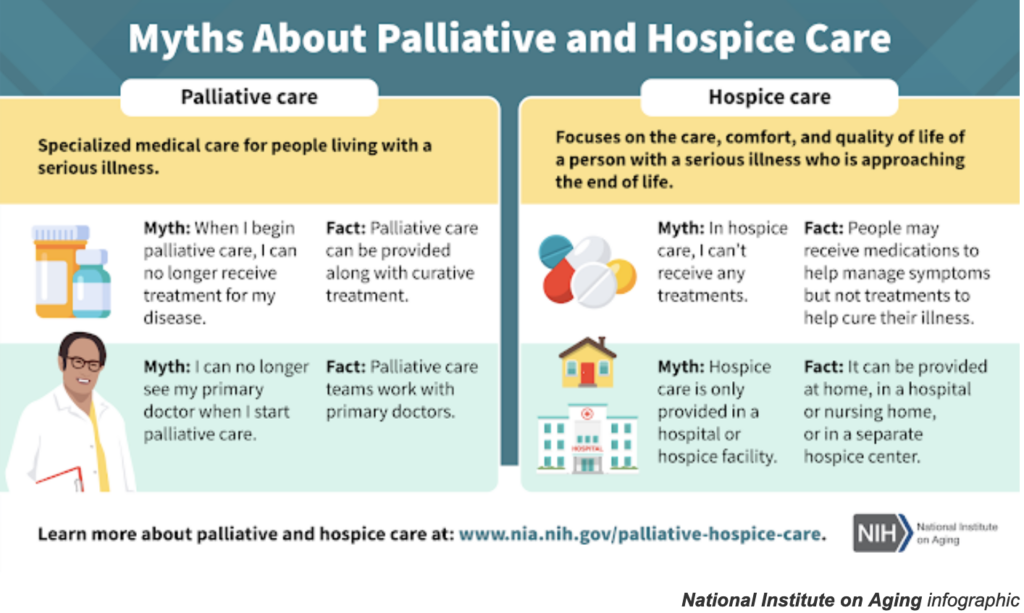

In contrast, “palliative care” or “comfort care” aims to make patients more comfortable and ease stress but can be done while doctors are still seeking to cure a disease.

Added to the confusion, the authors write that sometimes life-prolonging and palliative therapies can overlap, such as the use of diuretics for people with heart failure or radiation to relieve pain by shrinking a tumor.

Myths and fears about hospice still abound, Joan Teno, a Brown University hospice physician and researcher, told the Post.

“There’s very few people who say, ‘I wish I had started hospice later,’” Ben Marcantonio, interim CEO of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, told the Post.

End-of-the-year holidays produce a surge in calls about hospice when families gather and physical and mental decline can become apparent, Novas told the Post. The Carters have provided a lesson in what to do next.

“The Carters are doing a fantastic job in continuing to educate us,” Novas said. “Throughout their lives, and now in their deaths, their legacy will be teaching us about mental health and how to live and how to die well.”

People seeking advice about hospice can contact the Hospice Foundation of America’s Ask an Expert service at https://hospicefoundation.org/Ask-HFA [hospicefoundation.org] or by calling 202-457-5811 or 800-854-3402.